|

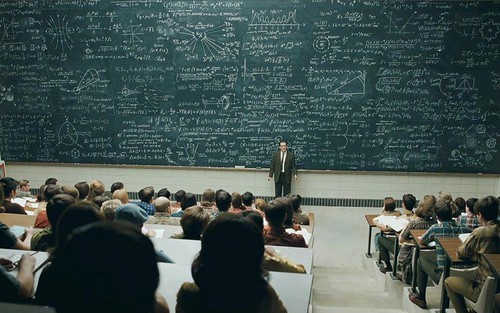

| Photo by Dom Fou on Unsplash |

During my schooldays and even at university I believed that I would be assessed on how well I remembered what the teachers told us in class. We were lead to believe that anything the teacher "went through" in class could come up in the exam. What we read in our textbooks was supplementary knowledge. The teacher probably also felt obliged to cover all possible questions to avoid accusations after the exam that "you never mentioned that in class". I taught for many years using this model and tried to cram in as much useful information as possible into my lessons in the belief that this was how the students learned best. So we were all locked in this information transfer illusion of learning that is still very common in education all over the world. Even if active learning and flipped classroom have become accepted and widely used, the default is still the traditional lecture.

This is discussed in an article by Harald Liebich in the Norwegian higher education news site Khrono (just use a translation tool), Er forelesningen et ritual eller en læringsarena? (Is the lecture a ritual or a learning arena?). Whenever the media or popular culture want an image to represent higher education it is nearly always the lecture hall with the professor on stage. He describes how lectures simply repeat what is much better described in a textbook and that students remember very little of value. A method with such limited impact on students' learning must be questioned.

The time invested by lecturers and students does not correspond to the intended outcome; the enhancement of learning. The limited impact of initiatives to implement innovative teaching methods can be linked to the lack of incentives for pedagogical development in the whole university sector. [My translation]

Forelesers og studentens tidsbruk står ikke i forhold til hovedintensjonen; læringsutbytte. Manglende drivkraft til å fornye undervisningsformene, kan ha sammenheng med at undervisningsarbeid gir begrenset merittering innen universitetsfeltet.

The lecture is indeed a ritual and should in most cases be transformed into an arena for group work and discussion. At the same time, I wonder if the ritual element still has relevance in terms of creating and cementing a sense of belonging. Attending a lecture every week reminds students that they are part of the university as an institution and reinforces a sense of pride and tradition that should not be underestimated. You may not learn so much but simply being there gives you a sense of identity just as walking about the campus or chatting in the cafeteria. I know that many people prefer to study in the library even if you could easily do so more comfortably at home. Somehow the library feels more academic, more inspiring, more serious. Also you can see lots of other people studying and you want to blend into the studious ambiance. This was transformed into an online setting during the pandemic with sites like StudyStream where you could join a silent video meeting, watching other students studying at their desks.

Lectures have a role to play but only is used sparingly. Liebich quotes an article in the journal Health Professions Education, On the Use and Misuse of Lectures in Higher Education, that reviews research in the value of the lecture and describes the methods limitations. However, there are times when a lecture can be valuable, especially as inspiration. The lecturer's role is not to provide content but to offer different perspectives and insights into their own research process. The vital element is to offer reflection, experience and inspiration - basically to tell an engaging story.

Articles describe only the end product of a scientific endeavor and do so in a static and formal way. Students however deserve to hear the whole story; the story of how the researcher developed a particular hypothesis, the story of the difficulties the researcher encountered, and his or her emotions when a cherished hypothesis turned out to be false. Who can tell these stories better than the researcher him- or herself? These narratives should be told and the lecture is a good place to do just that, in particular if the lecturer knows how to tell a good story.

The lecture may be an academic ritual but if the speaker can offer this story-telling element and convey enthusiasm and commitment to the subject matter it can also play an important role in the students' development.